On why she has been so deeply inspired by Buckminster Fuller's ideas and how they are still relevant today...

Date Posted

March 26, 2019

Emma Allen, founder of cult skincare favorite Everyday Oil, has been deeply inspired by Buckminster Fuller, the wildly prolific architect and theorist whose ideas and innovations include the Geodesic Dome and ‘Spaceship Earth’. In fact, Fuller created many of his most notable designs while teaching at Black Mountain College, an Appalachian outpost of the avant-garde, just a couple of miles up the road from Emma’s home in North Carolina. Here, Emma writes a letter from Black Mountain about why she is so drawn to Fuller’s ideas and how they are still relevant today.

Every now and then things show up in your life and make themselves known. For me, lately, that has been Buckminster Fuller. When I lived out at the tip of Long Island I worked with LongHouse Reserve, a sculpture garden in East Hampton, and they have a giant beautiful Buckyball on the grounds. I would often lie in it in the grass, seeing the way the sun made shadows through it. It felt special instinctively to me, but I didn’t know a lot about Fuller.

Courtesy Emma Allen

I set up my business, Everyday Oil, in Black Mountain, NC last year—right near where Black Mountain College used to be. So many of my heroes studied, lived and worked there, and it has been a good feeling to be in their vicinity in these mountains—Buckminster Fuller, Joseph and Anni Albers, Ruth Asawa, Robert Motherwell, Cy Twombly, Allen Ginsberg, Merce Cunningham, William and Elaine DeKooning—it is amazing to know that they all gathered in this place.

Hillary Falduto joined the Everyday Oil team this year and a little while ago we were driving back from lunch and passed a sign in town about Buckminster Fuller and his time in the area. I mentioned how I wanted to read more about Fuller and Hillary said he had come up a lot in her life as well. She grew up near where Fuller’s house was when he was a professor in Carbondale from 1959-1971. He was a research professor at the School of Architecture at SIU. When she lived there, it was overgrown with weeds and no one seemed to care that it was there. More recently it has been restored and is a little museum you can tour.

I had just ordered a copy of the Whole Earth Catalogue on eBay and Fuller’s books were all described in it as well, sitting on our coffee table. We came back to work and did a deep dive on Fuller, laughing at all of the synchronicities, finding a kindred spirit through time and space.

A week later I got a message in my inbox on Instagram from someone I had never met asking me if I would be interested in doing a post on Buckminster Fuller, since I am in Black Mountain—the universe!

Early in his life, Fuller went through a series of hardships, losing his job and having trouble providing for his family. His daughter passed away at the age of 3, and Fuller suspected it had something to do with his damp and drafty living situation. He would take long walks around Chicago reflecting on what to do, considering suicide as an option so his family could collect his life insurance payment. During this time, he said he experienced a profound incident – he felt suspended in the air, enclosed in a white sphere of light, and a voice said to him

From now on you need never await temporal attestation to your thought. You think the truth. You do not have the right to eliminate yourself. You do not belong to you. You belong to the Universe. Your significance will remain forever obscure to you, but you may assume that you are fulfilling your role if you apply yourself to converting your experiences to the highest advantage of others.

He says this experience made him profoundly re-examine his life and purpose, deciding to conduct “an experiment, to find what a single individual [could] contribute to changing the world and benefiting all humanity.”

This led him to “the search for the principles governing the universe and help advance the evolution of humanity in accordance with them… finding ways of doing more with less to the end that all people everywhere can have more and more.”

Fuller referred to himself as “the property of the universe” and “the property of all humanity.”

In 1954, potentially inspired by the death of his daughter, he patented the geodesic dome, seeing it as a low-cost, safe housing structure aligned with his mission to “make the world work for 100 percent of humanity in the shortest possible time…without ecological damage or disadvantage to anyone.”

Fuller was a futurist and envisioned a world with a new order not based upon exploitation of the masses. In his book Critical Path, he looks at the evolution of “lawyer-capitalism” in the world, and its dogma of scarcity, upon which modern economic theory is based. He proposes new options for humanity where humans provide for themselves with sustainably high living standards, derived entirely from renewable energy sources.

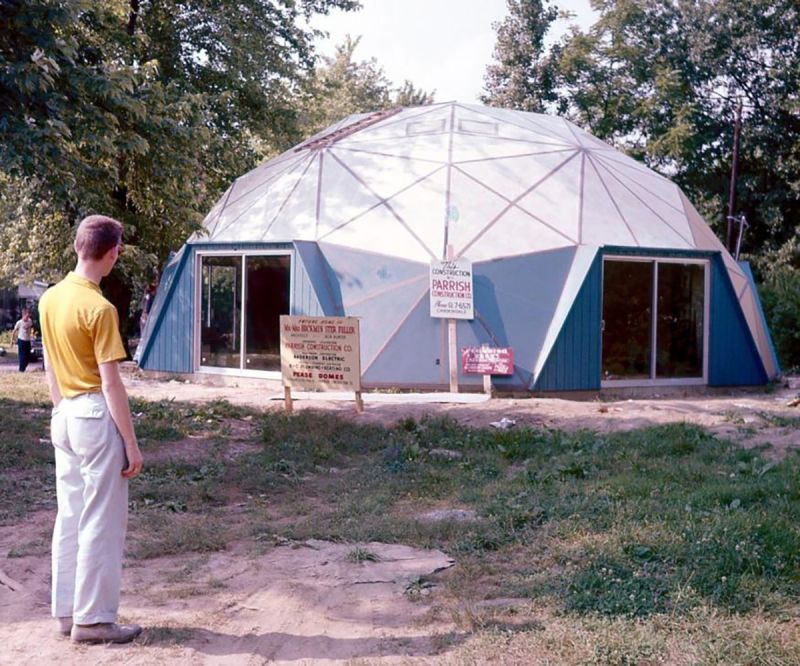

Fuller and team students, demonstrating the strength of the design

Desovereignization is a process stemming from the inevitable effects of globalized communications and trade—and is already very far advanced in the world today. Fuller asks “how big can we think?” and likens humanity to a chick that has just broken out of its shell, and is ready to enter into its next phase of existence.

He was an early environmental activist and promoted a principle that he termed “ephemeralization”, which he coined to mean “doing more with less.” He also created the term “spaceship earth” based on the idea that the Earth has a finite amount of resources and we are all astronauts who must take care of it to survive.

Fuller believed human societies would soon rely mainly on renewable sources of energy, such as solar- and wind-derived electricity. He hoped for an age of “omni-successful education and sustenance of all humanity.” He envisioned a “regenerative landscape” where, to take advantage of potential wealth, humanity should give fellowships to each person who is unemployed. He believed that for every 100,000 fellowships given out one person would come up with something so valuable to humanity that it would pay for the cost of the program.

This is only a fraction of Fuller’s huge body of work. For my part, doing more with less feels like exactly what the ethos of Everyday Oil is. And in our small ways we are trying to shy away from exploitative capitalist structures—inside of our company and in how we relate to our customers. Bucky inspires us to do better, to think bigger, and to keep following the threads that lead us to him and his guiding principles. It feels a little like Fuller’s time here in Black Mountain had become overgrown with weeds like his house in Carbondale—and like the energy of that time has lain dormant for a while. I hope here and in all our corners we sweep out the cobwebs and take a second look. Now seems to be the time.

Fuller at Black Mountain College